Get Free Copy Of Our Ad Testing Guide

Download PDFAd Testing is comprised of both math and creative elements.

At a high level, the steps to ad testing are quite simple:

However, it’s easy to use non-statistically relevant data or incorrect testing metrics if you don’t understand exactly what you want to know and how to measure how users interact with your ads.

In this guide, we’ll walk you through how to ensure you are using the correct metrics, data, and math so you are confident that your ad testing results will improve your account and that you aren’t making changes due to pure randomness or testing metrics that don’t help you reach your goals.

When you are ‘scientifically testing’; you are testing a hypothesis or idea.

The hypothesis is generally formed around an idea you have and something you want to learn about your customers.

For instance, you might try adding a 10% discount to your products. However, when you sell at a discount, you need to make up for it in more total orders to offset the lower price. So your hypothesis could be as basic as:

We believe that adding a 10% discount to our goods will increase conversion rates by 15% and the net revenue increase will be greater than $10,000. To test this, we will start off by offering a discount on a limited selection of

products and echo the discount in the ads and landing pages.

The hypothesis could be based upon a new business milestone: We’ve now sold more than 1 million tickets. We want to test if the credibility of adding “more than 1 million tickets sold” to our ads performs better than our current

call to action “Call for quick, personal assistance”.

The possibilities are endless; but here are some ideas to get you started:

Once you have determined what to test, the next step is determining the scale of the test.

Before you start testing your hypothesis; you need to know the scale of the test.

That brings us to the two different types of ad testing:

With single ad group testing, you examine the ad data for only that ad group. Even if you are testing in thousands of different ad groups, you will only examine the ad data within the ad group itself.

With multi-ad group testing, you examine the data at the hypothesis level (which can be an ad line, template, label, a pattern, etc) across all the ad groups where you are running a test.

When you consider your ad data, you should be thinking about the insights gleamed from any ad tests and if that data can be used elsewhere in your account.

For instance, if you run a test within a single ad group; you will know the best ad for the targeting in that ad group (targeting can be keywords, lists, placements, etc). However, you won’t know if that ad will perform well in

another ad group until you test it in the other ad group.

WIth multi-ad group testing, you are testing an idea across many ad groups and therefore, you will understand what line (or concept) is best across all the ad groups used in that test.

Advantages:

Disadvantages:

Advantages:

Disadvantages:

If you are testing very high value targets, such as brand terms or your hero keywords; then it is best to use single ad group testing as you will find the best ad for each targeting type.

If you are testing ideas, templates, or massive accounts and want insights that can be applied to many ad groups, and even landing pages or other marketing channels, then multi-ad group testing is best.

Once you have determined your hypothesis and where you will test, the next step is to choose what metrics will tell you that your ad tests are winners and losers.

If you have the maximum number of assets in an RSA, your ads can be rendered in more than 40,000 different combinations. Unless your ad group receives millions of impressions each month, the algorithms have to ‘guess’ at the best ad combinations to show and cannot fully rely on machine learning due to a lack of data.

Pinning assets will lower the possible ad combinations, allowing you to have more control over how your ads are displayed and increase the data density for machine learning to understand which ad combinations are performing best in your account.

Ad Strength is related to Google’s ability to control your ads and the variety of assets that Google can use to render your ads. Pinning assets lowers Google’s ad serving control and thus also lowers your ad strength.

Ad Strength is not related to your metrics or Quality Score. The only time Ad Strength matters is when at least two RSAs are in an ad group. When that occurs, the higher Ad Strength RSA usually receives more impressions. Due to how insignificant Ad Strength is to your account’s goals, this number can be largely ignored.

Ad Testing has always been an essential part of PPC management, and RSAs have not replaced the need for this activity. With RSAs, there are more testing methods available than with ETAs, so you should learn the various ways that you can test RSAs to improve your account’s effectiveness.

This is also known as a fully pinned vs. unpinned ad test.

If you have an unpinned RSA in an ad group, that ad will have shown for many combinations. Some of those combinations will have good results, and others will have poor results. However, Google does not give you the stats by ad combination to understand how your combinations perform.

To see how an individual combination is performing versus your RSA so that you can improve your asset usage or remove poor-performing assets, follow these steps:

Once you have achieved statistical significance, you can analyze the data to see if you should utilize more pinning or remove poorly performing assets from your RSAs.

This is also known as an unpinned vs. partially or fully pinned ad test.

When you have a specific headline that you want to see how it performs against Google’s algorithm, you can setup a test using this methodology:

This test will show you how your specific headlines performed versus Google’s algorithm.

These are commonly partially or fully pinned vs. partially or fully pinned ad tests.

If you are a good copywriter, you can usually produce better ad copy than machine learning. This test is also good for those who preferred the control that ETAs offered.

To create this test, follow these steps:

Often, each of these RSAs will have a different theme to them, such as one focusing on calls to action and another on authority statements, or one is focused on prices and another on discounts.

This testing method allows you to use some machine learning as you can have multiple assets for each headline, while also lowering the total combinations possible, to give the machine more data for each combination.

If you only want to test the theme and let the machine learning manage the other aspects of the ad combination, then you can only pin 1-3 headlines to a specific position in multiple RSAs.

With either method, once you have achieved statistical significance, you can pause the loser ad and see which type of combination or theme produced the best results for your account.

You can also test RSAs by creating 2-3 unpinned RSAs in an ad group and let Google serve the ads as they like. With this method, it is best if you have hundreds of thousands of impressions in your ad group each month. A fully unpinned RSA can serve for more than 40,000 combinations. If you have 3 unpinned RSAs in an ad group, that means there are more than 120,000 possible ways Google can serve your RSA. If you do not have a tremendous amount of impressions, machine learning will never have enough data to understand the ad test.

If you have that many impressions, then you can use this method to test various RSAs and pause your losers as they occur.

If you want to gain insights across multiple ad groups using RSAs, then you can label each RSA ad test and aggregate your data across labels.

If you are testing two different themes across multiple ad groups, you can label the RSAs within each ad group by its theme. For instance, if you were testing authority statements versus calls to action in your headline 2s, then you can add a different label to each ad based on that theme in every ad group you are testing. Once these labels are in place, then you can aggregate the data for each label to understand how these two different themes compare.

Once you have determined your hypothesis for testing; you next need to determine how to pick winning ads.

Once you have determined your hypothesis for testing; you next need to determine how to pick winning ads.

We’ll briefly walk through the metrics here; and if you would like to learn more about each individual metric, please see the detailed article.

We recommend that most advertisers use impression based metrics.

When you are running ad tests, there are generally six different metrics that you can use to determine winners; however, the way they are used can be very inconsistent, and some metrics are misunderstood. It is important to understand the basics of all the testing metrics and their overall pros and cons.

CTR is the ratio of clicks to impressions. Using this metric ensures that you receive the most clicks possible.

Quick Pros:

Quick Cons:

Conversion rate is the ratio of conversions to clicks. This metric ensure you receive the most conversions possible of the clicks you receive.

Quick Pros:

Quick Cons:

Cost Per Acquisition is the ratio of spend to conversions. This metric is simply how much you paid to get a conversion.

Quick Pros:

Quick Cons:

Conversion per Impression is the ratio between conversions and impressions. It ensures you get the most conversions possible for the impressions you receive.

Quick Pros:

Quick Cons:

ROAS is the ratio of revenue to spend. It ensures that you maintain minimum margin on your sales. It is most commonly used for ecommerce sites.

Quick Pros:

Quick Cons:

Revenue per Impression is the ratio of revenue to impressions. It ensures you receive the most revenue possible for the impressions you receive. It is most commonly used for ecommerce sites.

Quick Pros:

Quick Cons:

There are many times that you should be using two metrics when testing to ensure your ad testing is helping you to achieve your goals.

For instance, if you are an ecommerce account with this simple goal:

In this case, you need to examine two metrics at the same time to determine winners:

That simple process will make sure that you are achieving your goal of maximizing your within your target ROAS.

You should choose how you pick winners before you start a test so that you understand what metrics to monitor. To read about a specific metric in detail; or to get details on all the metrics, please continue reading this guide.

CTR is the metric that Google pushes you to use the most as their ad rotation default is set to optimize for clicks, which is the highest click through rate ad. This metric is useful to use for ad testing when you want to increase traffic or one of your primary goals is visitors. However, as it does not take into account conversions or revenue goals, it is often not a great for sites that are trying to gain new customers from PPC advertising.

CTR is simply the ratio of impressions to clicks.

CTR is calculated by diving the number of clicks by your impressions:

CTR = clicks/impressions

It is generally displayed as a percentage. Here are some examples:

| Ad | Clicks | Impressions | CTR |

| 1 | 45 | 243 | 18.52% |

| 2 | 97 | 1023 | 9.48% |

| 3 | 56 | 840 | 6.67% |

| 4 | 32 | 230 | 13.91% |

In this case, ad 1 has the highest CTR and ad 3 has the lowest CTR.

There are two main reasons to use CTR as your testing metric:

If your goal is to get more traffic, have more people see your site, then CTR is the best metric to use for testing. This is a common metric to use for brand departments who want to make sure that people are seeing their offer. It is also common to see companies use CTR for their branded keywords and another metric for their other keywords.

If you are struggling with Quality Score, then using CTR as an ad testing metric can often help in increasing Quality Score. As CTR is one of the most important factors in Quality Score, having high CTRs often correlates to higher Quality Scores (and often lower CPCs). It is common to see an account where there is a direct correlation between CTR and Quality Score.

For instance, here’s a chart for one account where the metrics are broken up by Quality Score ranges. The trend between higher Quality Scores with higher CTRs is a very common occurrence.

| Quality Score | Clicks | Impressions | CTR |

| 1 | 0 | 0 | 0% |

| 2 | 1 | 143 | 0.70% |

| 3 | 21 | 3094 | 0.68% |

| 4 | 1036 | 164,582 | 0.63% |

| 5 | 471 | 23,289 | 2.02% |

| 6 | 7563 | 353,377 | 2.14% |

| 7 | 59,593 | 1,530,468 | 3.89% |

| 8 | 68,153 | 1,435,300 | 4.78% |

| 9 | 93,640 | 1,329,169 | 7.05% |

| 10 | 131,586 | 1,472,395 | 9.62% |

| Totals | 372,064 | 6,301,816 | 5.90% |

Therefore, if your main goals are to increase Quality Scores or receive the most traffic, CTR is a good metric to use.

While CTR is good for getting large amounts of traffic; what it doesn’t do is discriminate against good or bad traffic.

For instance, if you have a high CTR and a very high bounce rate; then you’re just attracting traffic that does not care about your message. Therefore, even when you are trying to get the most traffic possible, its best to use interaction goals (such as page views per visit or time on site) to make sure you are receiving quality traffic. Thus, CPI (conversion per impression) is a better metric to use than CTR when your goal is high quality traffic. With CPI, you can set a goal based upon a quality visit and then optimize your ads to attracting the most qualified visitors as opposed to just the most visitors.

Raising CTRs to increase quality scores is good for most companies; but not necessarily all of them. In many cases you use your ads to qualify users before they click on your ad. If you remove the qualification, then your CTR and quality score will often increase, but at the detriment of your overall goals.

For instance, in the B2B (business-to-business) space, it is common to add qualifications to ads, such as an account adding “for businesses” or large commercial sales adding “industrial” to the ads. The goal of those qualifications is to clarify to the user that your offer is specific to businesses and not to consumers. When you remove those qualification, you do often see some metrics (Quality Score & CTR) increase, but your sales staff is generally unhappy as they aren’t receiving as many leads or the ones they do receive are not qualified.

Examining CTR is useful when combined with other metrics in order to break ties. For instance, if you have two ads with identical metrics (such as CPI, CPA, CR, ROAS) and you’re not sure what to pick, choosing the higher CTR ad will generally result in higher quality scores and thus slightly higher positions (so more traffic) or lower costs.

If you care about the quality of your traffic, the CTR is never a good testing metric to use. In those cases, you should use a goal (such as time on site) and CPI (conversion per impression) as your testing metric.

If you care about actual conversions, then CTR is never a good metric to use by itself as it doesn’t use conversions or revenue in its calculations.

If you are struggling with raising quality scores, then CTR can be a great metric to use in your testing.

CTR is important. Without clicks, you won’t receive any conversions and the other metrics are moot. However, CTR is rarely a metric you will use by itself in your testing, yet it is a great stat to use as a tie breaker when you are also testing by other metrics such as CPA.

Conversion Rate is commonly used for testing as the higher your conversion rate, the more conversions you have once someone clicks on your ad. The biggest downside to conversion rate is that it doesn’t take into account how many clicks your ad actually receives.

Conversion rate (CR) is simply the ratio of clicks to conversions.

Conversions rate is calculated by diving the number of conversions by your clicks:

Conversion Rate = conversions/clicks

It is generally displayed as a percentage. Here are some examples:

| Ad | Conversions | Clicks | CR |

| 1 | 1 | 100 | 1% |

| 2 | 10 | 100 | 10% |

| 3 | 32 | 1045 | 3.06% |

| 4 | 57 | 1103 | 5.17% |

In this case, ad 2 has the highest conversion rate and ad 1 has the lowest.

There are two main reasons to use CR as your testing metric:

A common landing page testing method is to use two identical ads in an ad group with the exception of the destination URL. If you are testing landing pages, then ad 1 goes to landing page 1 and ad 2 goes to landing page 2.

If you are testing page templates, then you might duplicate this test across several ad group and use multi-ad group testing to aggregate the results across all of your ad groups by page template.

The other reason to use conversion rate as a testing metric is when you want the most conversions possible once someone clicks on your ad. We have to qualify this very carefully as conversion rate has an inherit weakness – it doesn’t care about the volume of clicks.

While conversion rate is great for landing page testing, it is not a good metric to use for increasing total conversions from your PPC ads since it doesn’t care about how often your ad is actually clicked. Consider these stats:

| Ad | Impressions | Clicks | Conversions | Cost | CTR | Conv Rate | CPA |

| 1 | 1000 | 100 | 10 | $200 | 10% | 10% | $20 |

| 2 | 1000 | 10 | 2 | $25 | 1% | 20% | $12.50 |

| 3 | 1000 | 56 | 5 | $126 | 5.6% | 8.93% | $25.20 |

| 4 | 1000 | 11 | 4 | $33 | 1.1% | 36.36% | $8.25 |

| 5 | 1000 | 156 | 12 | $234 | 15.6% | 7.69% | $19.50 |

In every case, these ads all received the exact same impressions. Because CTR varies, so will the actual CPC and costs for each ad variation.

The ad with the absolute highest conversion rate is ad test 4 at a 36.36%. However, that ad only received a total of 4 conversions. The ad with the lowest conversion rate, test 5, received three times as many conversions at 12. Because ad 5 had such a high CTR, it received more traffic than the other ads and therefore, it had more opportunities to create conversions. So even though it’s the lowest conversion rate, it ends up with the most conversions.

When conducting ad tests, conversion rate is rarely, if ever, a good metric to use as your sole decision in deciding which ad is best for your PPC account. Conversion rate is a good metric to combine with CTR, which creates CPI (conversion per impression) which will be a featured metric later.

For landing page tests, conversion rate is a good number as landing page testing only cares about the traffic that reaches the page; the page itself does not attract more or less clicks – it only cares about the user who actually reached your page.

Conversion rate is a very important metric – I don’t want to discount its importance as a metric in ad testing. However, since conversion rate doesn’t care about the ratio of clicks at all, it is not a great metric to use for ad testing by itself. It is very good when combined with click through rate, which then creates the metric Conversion Per Impressions (CPI).

Where conversion rate is your go-to ad testing metric is when you are testing landing pages and not the ads. If your ads are identical and you are just testing landing pages; then conversion rate will be your primary metric in your testing.

Don’t discount conversion rate as a metric, but unless you are testing landing pages, do not use it as your sole metric for determining ad winners.

CPA (cost per acquisition) is simply how much you pay for a conversion.

This of often called cost per conversion; however, in PPC, we usually associate the acronym CPC with cost per click, so it is common to someone say ‘Cost Per Conversion, our CPA’ to avoid confusion.

This a common metric to use for testing in a few different types of accounts:

Here’s a few examples of business models that should be examining their CPAs:

Some ecommerce accounts have checkouts that are highly variable and ROAS (return on ad spend) doesn’t work as a testing method, in which case CPA is a good metric to use. For instance, I work with one ecommerce company whose average checkout is roughly $500. However, 5% of their checkouts are for more than $10,000. The keyword and ad that receives those high value checkouts are completely random and there is no pattern. Thus if they were to use ROAS as a bid or testing method the random checkouts would lead to them picking an ad winner that might not lead to the same value the following month; and thus CPA is a better metric for them to use for testing and bid management.

Often with CPA testing, you won’t use just CPA as your testing metric, it’s a great combination metric to use and we’ll address that later in this article.

CPA is how much a conversion costs you.

CPA is calculated by dividing total cost by total conversions.

CPA = cost / conversions

It is generally displayed as a percentage. Here are some examples:

| Ad | Cost | Conversions | CPA |

| 1 | $1,000.00 | 10 | $100.00 |

| 2 | £1,000.00 | 5 | £200.00 |

| 3 | ¥500.00 | 10 | ¥50.00 |

| 4 | € 429.00 | 11 | € 39.00 |

If we don’t correct for the currency differences and assume these were all in the same currency, then ad 4 would have the lowest CPA and ad 2 would have the highest CPA.

The primary advantage of using CPA is to control costs and how much a conversion costs you.

For instance, if you are reselling leads for $25, then you might not want to pay more than $15 for a lead.

If you have a long sales cycle, then often you need to do the math throughout the cycle to determine your short term CPAs. For example, let’s say that your sales cycle is:

Let’s assume we spent $10,000 at $1 CPC and see how much it costs to close the lead:

| Conversion rate | People in funnel | CPA | |

| Clicks to site | 10,000 | ||

| Emails collected | 20% | 2,000 | $5 |

| Accept webinar invite | 40% | 800 | $13 |

| Attend webinar | 50% | 400 | $25 |

| Watch 50% of webinar | 50% | 200 | $50 |

| Sales team contact rate | 25% | 50 | $200 |

| Sales team close rate | 20% | 10 | $1000 |

From this information we could work backwards to determine our initial CPA for email collection. If the cost of $1,000 for a new sale is profitable, then we’re in good shape. If we want to increase the people entering the funnel, we can raise the CPA. If the final cost is too low, then we can lower the CPA.

Now, in this particular case, there are many things you can test beyond the ad’s CPA, such as:

In some cases, this is much easier. For instance, if you sell a single digital product for $50, you might be OK with a $40 CPA as that will net you a $10 profit on each sale. CPA can be complicated to determine at times; but when you want to watch your costs, CPA is a good metric to use either by itself or in conjunction with other testing metrics.

While CPA is great for controlling costs, it isn’t always the best metric to use for testing since it doesn’t take into account the volume of clicks or the conversion rate.

Consider these stats:

| Ad | Impressions | Clicks | Conversions | Cost | CTR | Conv Rate | CPA |

| 1 | 1000 | 100 | 10 | $200 | 10% | 10% | $20 |

| 2 | 1000 | 10 | 2 | $25 | 1% | 20% | $12.50 |

| 3 | 1000 | 56 | 5 | $126 | 5.6% | 8.93% | $25.20 |

| 4 | 1000 | 11 | 4 | $33 | 1.1% | 36.36% | $8.25 |

| 5 | 1000 | 156 | 12 | $234 | 15.6% | 7.69% | $19.50 |

For these results, each ad was served the same amount of times (1000). The lowest CPA is ad 4 at $8.25; however, it only has 4 conversions. The ad with the most conversions is ad 5 with 12; but it’s CPA is more than double the lowest CPA ad.

This is often what you fight with CPA – costs versus volume.

Where CPA is a great metric is when you combine it with other metrics.

In many cases, you don’t want the lowest CPA ad – what you want is to set a threshold for your target CPA and then pick the ad with the most conversions that is at or below your target CPA.

For instance, if our max CPA was $20 this would be our process:

Now, the biggest issue in the real world with this process is that all your ads won’t have the exact same number of impressions. Thus in reality what you usually do is eliminate the ads above your target CPA and then pick the highest CPI (conversion per impression) ad as that will lead to the most conversions at or below your target CPA.

In some cases, you will have a target CPA, but you want the most visitors to see your offer (landing page) and become familiar with your company. This is a common tactic for PPC accounts where many searchers will visit the site multiple times before they convert. In that case, you would use CPA as your filter and then user CTR as your winning ad metric. This is also useful if you are trying to raise quality score (higher CTRs usually mean higher quality scores) but you have a max CPA that you to optimize to at the same time.

CPA is a very important metric for most accounts (some ecommerce being the exception) as it determines how much you pay for a conversion. You can compare that data to your actual revenue per conversions and ensure that your PPC account is profitable.

The downside of CPA is it doesn’t take volume into account (such as CTR or conversion rates); and thus while it’s a great metric to know and use, it is rarely a metric you will use exclusively in your ad testing. What CPA is great for is filtering ad tests. Use CPA as a filter to remove ads that are above your target CPA; and then you can use another metric, such as CPI or CTR to determine the winner of the ads that are within your target CPA.

This combination of using CPA as a filter and another metric to determine a winner of ads that are left is a great way to ensure that your account is profitable and that you are maximizing the other goals your account has, such as most conversion, most clicks, etc.

CPI (Conversion per Impression) is a metric that shows the ratio between impressions and conversions.

When you consider ad testing, which combination is better?

It’s impossible to say which is better since that information relies on two different metrics: CTR and Conversion rate.

What CPI does is combine these two different metrics to form one single metric that will show you which ad will receive the most conversions from the impression.

Every time your ad is displayed; you have a chance of a conversion. You picked a keyword. Someone searched for your keyword. At this point in time there’s a chance of a conversion. The user must both click on your ad and then convert to receive the actual conversion; but measuring from the impression shows you the total conversions possible.

CPI is calculated by dividing total impressions by the total conversions.

CPI = conversions / impressions

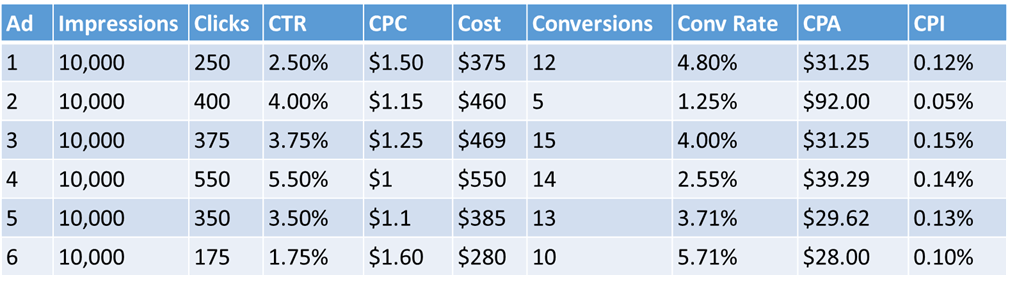

It is generally displayed as a percentage. Here are some examples:

| Ad | Impressions | Conversions | CPI |

| 1 | 10,000 | 12 | 0.12% |

| 2 | 10,000 | 5 | 0.05% |

| 3 | 10,000 | 15 | 0.15% |

| 4 | 10,000 | 14 | 0.14% |

| 5 | 10,000 | 13 | 0.13% |

| 6 | 10,000 | 10 | 0.10% |

In this example, ad 3 has the highest CPI and ad 2 has the lowest Conversion per Impression.

The main reason to use CPI is when you want the most conversions possible. As this metric takes into account both CTR and conversion rate, it’s a simple metric that will show you which ad will lead to the most total conversions possible.

There are times that when you examine the full metrics behind various ads, you might not always pick the highest CPI winners. This usually happens for a few reasons.

Let’s take a look at a full chart of data and then examine how we’d pick the various winners (click the chart to see a larger version).

If we just want the most conversions possible; then ad 3 is our clear winner. It receives 15 conversions for every 10,000 impressions. This is why CPI is such as great metric. Ad 3 is not the winner in CTR (that’s ad 4) or the winner in conversion rate (that’s ad 6). In comparison to our other ads; ad 3 has both a good CTR and a good conversion rate, but it is not a winner or loser in either metric. However, when you use both CTR and Conversion rate to calculate the most conversions possible for and ad; then ad 3 is our clear winner.

If we are struggling with Quality Score; then we might pick ad 4 as it has a much higher CTR than the other ads, which is also why it has a lower CPC than the other ads, and its CPI is not too far behind our winner.

If our goal is a $30 CPA and we want the most conversions under $30; then we’d eliminate all the ads with a CPA higher than $30 and pick the highest CPI ad from the ones that are left as our winner; which is ad 5.

If we only wanted 10 leads a month and therefore, pay as little as possible for those 10 leads; then ad 6 would be our winner as it has the lowest CPA of all the ads and it can reach 10 conversions per month (assuming this was monthly ad data).

Assuming we want the most conversions possible, or even the most possible under a $32 CPA target, then ad 3 is our clear winner. However, we should learn from the other ads in our next set of ad tests. This is where examining ads that lost in your overall metric but won in a single metric is useful.

For example, ad 4 is a clear CTR winner. Why? Was there a line in the ad that was very attractive to users? We might want to use that line for our next ad test. We could duplicate ad 3, add that line, and then run another test.

Why did ad 6 have such a great conversion rate? It did have a very low CTR. Odds are, this ad was ‘pre-qualifying’ users with ad text that was meant to filter out users. We could look at what that qualification is, use it in a new ad 3 duplicate, and test that combination.

Finally, ad 2 was a conversion rate failure. Why? We might want to add a note about a line to avoid as this ad clearly attracted the wrong types of clicks.

The one downfall of CPI is that it doesn’t care about revenue or total order amounts. If you have an ecommerce site and want to base your conversions off of ROAS or revenue targets, CPI is not a great number to use.

CPI is great for lead generation, or the most conversions possible. However, since revenue and ROAS are not numbers used in its calculation, there are other metrics, such as ROAS or RPI/PPI (revenue/profit per impression) metrics that are better to use for ecommerce companies. We’ll cover these additional metrics later.

Conversion per impression is one of the best ad testing metrics you can use since it is a simple number that lets you see which ad will lead to the absolute most conversions.

The largest downside of CPI testing is that it does not take into account revenue per conversion. So while it’s a great metric to use for lead generation companies, it might not be suitable to ecommerce companies.

If you have hard CPA targets, then you can use CPA as a filter to remove ads that are above your target CPAs and then pick your highest CPI ad as your winner; so many companies should use both CPA and CPI testing metrics to choose their winners.

If you are not taking into account revenue for your testing metrics, then you should always evaluate CPI when determining your winners – it’s that good of a metric to use for your testing needs.

The next two metrics we need to discuss, ROAS and RPI (revenue per impression) rely on tracking revenue and often on talking about ROAS and ROI.

Before we get into those metrics, we need to examine how data is passed back and forth to your PPC accounts in order to use terminology that is somewhat in line with marketing and economic terms.

There is a lot of confusion about ROAS, ROI, and Google’s Conv. Value/Cost metric, we’re first going to dig into these metrics before proceeding to how to use them in your ad testing.

Return on investment (ROI) has been long misused in search. The true formula for ROI is ROI = (revenue – cost) / (cost).

This formula has been warped by many marketers into ROI = (revenue) / (cost) (please note that formula is not correct, we’ll cover the correct one in a moment). They choose to use this incorrect formula because ROI can be a negative number, and negative numbers make bid calculations more complex. A 100 percent ROI in the incorrect formula is your breakeven point (assuming you aren’t taking the cost of hard goods into account), so calculations become easy. The simple explanation for this is that since you are calculating marketing costs, you just removed those same costs from the formula to calculate ROI.

When search marketing was primarily conducted by non-marketing people in the early years when the web designer or IT department often ran paid search, this slight change in definition often did not matter to the company. However, as search has grown into a multi billion-dollar business and is being taught in college marketing classes, an effort must be made to correct the use of these terms so that it is consistent between company departments.

The ROAS formula is ROAS = (revenue / advertising cost). The ROAS formula is the same as the warped or incorrect ROI formula used by many search marketers.

While this difference doesn’t matter to everyone, if you ever run into a CFO auditing your numbers, they will care quite a bit about the difference in ROI vs ROAS.

Let’s take a simplistic look at the difference between ROI and ROAS.

| Campaign | PPC Cost | Revenue | ROAS | ROI |

| 1 | $1000 | $2000 | 200% | 100% |

| 2 | $1000 | $1000 | 100% | 0% |

| 3 | $1000 | $500 | 50% | -50% |

In this example, for campaign 3 to break even it needs to lower its bids by 50%.

By using ROAS as our bid multiplier, its easy math to do within Excel since ROAS is always a positive number (or 0); hence why ROAS is used by most marketers to set bids. If you use ROI, since the number can be positive or negative, you need to build a more complex formula to calculate your bids. In the end, the answer is the same: reduce your bids by 50% to break even.

This is why most PPC marketers actually use ROAS even if they say they are using ROI. Please note, this isn’t everyone – many people know the difference and are calculating these numbers correctly. However, at every conference I attend, at least one speaker uses the ROI term incorrectly.

If you are ignoring hard costs such as salaries and manufacturing, and if you are selling a digital good – then ROAS is usually a good number to work from and your ROAS is your actual ROAS.

However, if you are selling physical goods then you need to remove the cost of those goods from your revenue to calculate bids and determine ad test winners.

Please note, this cost of physical goods does not always have to be physical goods. If you are selling hosting packages, then you’d want to remove your costs for servers, bandwidth, etc as they are hard costs. However, there’s not an easy way to do this in Google Ads, hence why we’re going to stick to physical good examples since that can be programmatically accomplished.

Google Ads allows you to pass dynamic variables to your account based upon the sale. (Information on how to do that here).

Most advertisers are passing along the total sale of goods (excluding shipping) to Google Ads who are using this feature. In this case, ROAS is not true ROAS since the cost of goods is not being removed before the metric is calculated. This is why a lot of companies do not have a 100% break even ROAS. They might have a 200% ROAS target to break even since they have to accommodate for the cost of goods in their calculations. In these cases, the company might have a 400% ROAS target for the account to be profitable.

Some companies are passing total cost of goods sold minus cost of hard goods to Google Ads. In this case, ROAS really is ROAS (again, assuming you’re only talking goods and no other fixed costs).

If you are calculating actual ROAS, then a 100 percent ROAS is breaking even if you have 100% margins or are removing the cost of goods before calculating the number. If you are selling products and not removing the cost of those products, then a 100% ROAS means that you are losing the cost of the product, and potentially shipping, on each sale.

A 200 percent ROAS means for every dollar you spend, you bring in two dollars of revenue. A 50 percent ROAS means for every dollar you spend, you bring in only 50 cents. In other words, a 50 percent ROAS means you are losing money.

This is where calculating ROAS and ROI can be even trickier as we’re making the assumption that we’re only talking about the cost of goods and marketing costs. Some companies calculate revenue and profits by taking out all costs, which can include overhead, salaries, and so forth. So even within a company you might have two different calculations for the same metrics.

If you are passing revenue amounts into Google Ads then you can see your ‘Conv. Value / Cost’ numbers inside your Google Ads account.

This column is calculated by diving the total conversion value, which is the total revenue numbers you passed to Google for that data point (i.e ad, keyword, etc) by the cost of those same clicks.

Conv. Value / cost = Total Conversion Value / Cost.

If you hover over the ? icon in Google Ads, you’ll see this tooltip from Google:

Conversion value per cost (“Conv. value/cost”) measures your return on investment. It’s the conversion value divided by the total cost of all ad interactions. The cost in this metric excludes interactions that can’t lead to conversions, such as those that happen when you aren’t using conversion tracking..

Google states that this number is your return on investment (ROI). However, that’s not accurate as the formula that’s being used is the ROAS formula, not the ROI formula.

Please note, most people show ROAS and ROI as percentages. Google shows it as a whole number. So a 2750% ROAS is displayed in Google Ads as 27.5. These are the same number, only the display changes.

ROAS and ROI are simple ratio metrics. It is possible for one ad to have a higher ROAS than another ad, but have less profits.

Here’s a very simplistic look at two ads:

| Ad | Cost | Revenue | ROAS | Profit |

| 1 | 5000 | 10,000 | 2 | 5,000 |

| 2 | 3000 | 7,000 | 2.33 | 4,000 |

In this example, ad 2 has a higher ROAS but less profits. Ad 1 has a lower ROAS and higher profits.

It’s useful if you can to calculate profits along with ROAS for your campaigns. This is another reason that we like using revenue or profit per impression in our ad testing; and we’ll cover that metric soon.

When you are going to say ROI or ROAS, think back to what math which you are using for the basis of that statement. Is it your actual ROAS, your ROI, or some version of ROAS you use inside your PPC department for bidding that might not be your actual ROAS?

If your team has a 200% break-even ROAS, then you aren’t calculating ROAS. You might internally use the term ROAS as a way to describe your numbers, but this number is more akin to cost of revenue calculations (although, that’s not quite right either).

We’re going to discuss how to test by ROAS and Revenue/Profit per impression metrics. These are two great metrics to use for ecommerce accounts. However, we needed to first define ROAS and its various permutations before we can easily discuss how to use ROAS and RPI/PPI for testing purposes.

ROAS (return on ad spend) and ROI (return on investment) are two common methods of ad testing for ecommerce accounts.

If you are dynamically passing your conversion values to Google Ads; then you’ll have a column known as Conv. Value/Cost in your account. This stands for Conversion Value / Cost.

This value is calculated based upon how you’re passing data from your system to Google Ads. If you are passing the entire checkout amount (hopefully minus shipping); then this value is usually ROAS. If you are passing the checkout amount minus hard goods; then this value is generally ROI.

As these metrics can be confusing to work with, you can refer to the previous article on how ROAS and ROI are calculated in PPC.

Because this number in Google Ads is not always ROAS or ROI, we’re going to use Conv. Value/Cost as that’s what you see in your account.

Conv. Value / Cost is calculated exactly how you think it would be: It takes the entire conversion value of a data point, such as an ad, and divides that by the cost of that same data point.

Conv. Value /Cost = (total conversion value) / (cost)

While ROAS and ROI are usually expressed as a percentage; Google shows this as a whole number. Here are some examples:

| Ad | Conversion Value | Cost | Conv. Value / Cost |

| 1 | 100 | 300 | 0.3 |

| 2 | 500 | 500 | 1 |

| 3 | 1000 | 700 | 1.4 |

| 4 | 10,000 | 1000 | 10 |

| 5 | 15000 | 3500 | 4.3 |

In this example, ad 4 has the highest Conv. Value/Cost and ad 1 has the lowest.

There are two main reasons that companies like to use ROAS as their testing metric.

The first is bidding alignment. Many ecommerce companies bid based upon ROAS or ROI; therefore, using that same metric for their ad testing ensures that their ad tests are in alignment with their bidding goals.

The second reason is that it ensures the spend is profitable. Many companies require the account to have a positive ROAS, such as 400% to make sure that the account is making money. Often these numbers are inflated above their true goal as they might not be removing costs of goods or other costs from their account, so by inflating the target ROAS or Conv. Value/Cost above their true targets, they know the account or the ad test is making money.

The downside of using Conv. Value / Cost as a testing metric is that it doesn’t care about volume. For instance, what winner would you pick from this chart:

| Ad | Cost | Conv. Value | Conv Value /cost |

Profit (conv value – cost) |

| 1 | 100 | 1000 | 10.0 | 900 |

| 2 | 1000 | 5000 | 5 | 4000 |

| 3 | 1200 | 1000 | 0.8 | -200 |

| 4 | 800 | 5000 | 6.3 | 4200 |

| 5 | 5000 | 12,000 | 2.4 | 7000 |

If you picked the ad with the highest conv. value/cost, ad 1 at a 10; then you’re only making 900 in profit (assuming there’s no other hard costs).

If you picked ad 4, the second highest conv. value/cost then you’d make 4200.

If you picked ad 5, one of the lowest conv value/cost; then you’d make 7000.

So while ad 5 is best for the company, the highest conv. value over costs is actually one of the least profitable ads.

In many cases, our conv. value / cost isn’t actually all profit, its total revenue but hard goods aren’t removed (again, this depends on the data you’re passing to Google Ads) so your profit might not be profit, it’s really just revenue minus marketing costs. Therefore, you might have a conv. value target of 5 and your breakeven point is a 3.

In that case, ad 5 would lose you a lot of money since it’s actually below your breakeven point. Therefore, you have to filter out any words below a 3 Conv. Value/cost and then take the highest profit word after the filtering is completed, which would be ad 4.

The other option would be to first remove all hard costs, and then work from profit in picking your ad tests. Just note, that the highest conversion value/cost or even highest ROI/ROAS ads might not be the most profitable ones for the company. This is common when you place emphasis on high volume low margin ordering versus lower volume higher margin products.

Regardless, Conv. Value / Cost can be a great filter to remove ads that aren’t hitting your targets and then you can use other metrics to pick the winners.

Using Conversion value/cost is a decent testing metric if you want to align your bid method to your ad testing method.

Just remember that conversion value / cost is a metric in Google Ads that could correlate to ROI, ROAS, or even another metric depending on its configuration.

The downfall of Conversion Value / Cost is that it’s a ratio of revenue to spend. It does not take profit or volume into account.

Therefore, this is a good filtering metric to use to remove unprofitable ads before using another metric to determine your winning ads.

In our next article, we’ll discuss using RPI (Revenue per impression) as a testing metric. This is often a better metric to use for ecommerce accounts than conv. value / cost for picking the winners.

However, even using RPI, you might still use Conv. Value/cost as a filter metric first and then use RPI to pick your winners.

RPI (Revenue per Impression), sometimes called profit per impression (PPI) is a good testing metric to use for ecommerce accounts or accounts with variable checkout amounts.

The difference between RPI or PPI isn’t in the metric calculations within your PPC account. The difference has to do with how you are passing data to your Google Ads account and if you are using ROAS or ROI in your data, which we’ve previously covered.

In this article, instead of constantly saying revenue/profit per impression (depending on how you are passing data) – we’re going to be consistent and just use RPI and revenue. However, if you are taking out the cost of goods (or don’t have any hard costs) before you pass your revenue data to Google Ads; then you can substitute the word profit instead of revenue throughout this article.

RPI (revenue per impression) is a metric that shows you the ratio between your impressions and the amount of money you make. This is very similar to conversion per impression (CPI) with the exception that we are adding actual revenue into the equation and not just using conversion data.

When you consider ad testing, which combination is better?

It’s impossible to say which is better since that information relies on three different metrics: CTR, Conversion Rate, Revenue (or RPS – revenue per sale).

When you have variable checkout amounts, instead of using conversions, using revenue gives you a more accurate picture of how much money you are making and lets you accurately determine ROAS and Conv. Value/Cost. For items that are consistently sold – this is the best metric in most cases to use as its your actual sales data.

There is a time when using CPI or plain conversion data is better than using revenue in your testing and management: when you have random outlier sales that skew the data drastically and are not repeatable.

For example, an early ecommerce client of ours makes about 300 sales a month. Their average sale is roughly $500. However, of those 300 sales, roughly 10-20 of them are for orders that are over $10,000. Month over month – they get 10-20 high value orders that are much higher than almost any other sale on their site. The ads and keywords that bring in these sales are never the same month over month. The fact they will get a sale from a keyword or ad is predictable; however, the amount from the sale is unpredictable. Therefore, using revenue for bidding or ad testing metrics is a bad idea since the data one month will not be consistent with the data the following month. However, since the fact they will get a sale is predictable, just not the revenue from the sale, they are best off to use CPI (conversion per impression) in their ad testing and bid management.

Another exception is when you want the most customers possible regardless of their checkout amounts. For instance, if you are trying to build a customer base then you would be happier with 1000 sales at $10 ($10,000 in revenue) than 500 sales at $30 ($15,000 in revenue). This is also an exception case and not the common management for most companies.

Outside of those edge case scenarios, if you are in ecommerce or have variable checkout amounts (such as a hosting company, domain name, or even consulting packages), then using your actual revenue allows you to maximize your ad testing towards higher revenue and not just conversions.

We should understand that measuring revenue and what you are actually making is more important to most companies than just measuring conversions. As your ads can affect average order value, upsales, cross sales, etc – you want to measure how much ads are actually making you and not just how many conversions they are bringing to your PPC account.

The question for most people is: why should we measure from the impression?

If you think about it, every time your ad is displayed – you have a chance of a conversion. You picked a keyword. Someone searched for your keyword. At this point in time there’s a chance of a conversion. The user must both click on your ad and then convert to receive the actual conversion; but measuring from the impression shows you the total conversions and revenue possible.

RPI is calculated by dividing total impressions by the total revenue.

RPI = revenue / impressions

It is generally displayed as a currency type. Here are some examples:

| Ad | Impressions | Conversions | Revenue | Average Sale Amount | RPI |

| 1 | 10,000 | 12 | 1200 | 100 | 0.12 |

| 2 | 10,000 | 5 | 2500 | 500 | 0.25 |

| 3 | 10,000 | 15 | 1500 | 100 | 0.14 |

| 4 | 10,000 | 14 | 8400 | 600 | 0.84 |

| 5 | 10,000 | 13 | 7200 | 900 | 0.72 |

| 6 | 10,000 | 10 | 500 | 50 | 0.05 |

To make this an easy illustration, we used the exact same number of impressions for every ad. Rarely is this the case. However, since we used the same impressions, the highest revenue (ad 4) is the highest RPI (0.84).

This ad is not the highest ratio of conversions (ad 3) or the highest average sale amount (ad 5). Ad 4 is the highest revenue per impression – meaning when ad 4 is displayed, you make more money than any other ad.

If your focus is to maximize your revenue, then you would want to use ad 4 as your winner.

The Advantage of using RPI as Your Testing Metric

The main reason to use RPI is when you want the most revenue possible. As this metric takes into account both CTR and actual revenue, it’s a simple metric that will show you which ad will lead to the most total revenue possible.

There are times that when you examine the full metrics behind various ads, you might not always pick the highest CPI winners. This usually happens for a few reasons.

Let’s take a look at a full chart of data and then examine how we’d pick the various winners (click the chart to see a larger version).

If we just want the most conversions possible; then ad 3 is our clear winner. It receives 15 conversions for every 10,000 impressions. If our goal is the most conversions – this is our winner. However, it has a lower ROAS and RPI than some other ads.

If our goal is ROAS; then ad 1 is our winner. It’s also our highest converting ad. However, it has a low CTR and thus is going to have a poorer quality score than some of the other ads. It has a lower RPI and makes less money than some other ads. This is why ROAS is a good metric for bid management, but rarely for ad testing.

If we want the most revenue possible, then ad 4 is our clear winner. It’s the highest revenue and highest RPI (because the impressions are equal among all the ads).

A common way to also use RPI, since it doesn’t care about ROAS, is to use ROAS as a filter. For instance, you might have a goal of 500% ROAS. Therefore, any ads underneath that ROAS target can’t be a winner and you eliminate them. Among the ads that are left, the highest RPI would be your winner. If your goal was a 600% ROAS, then you’d eliminate ad 4 and of the ads left, ad 1 becomes the winner since it has the highest RPI among ads with at least a 600% ROAS.

You don’t want to throw away your data for all the losers. You always want to examine it to find other ideas to test. For instance, our highest converting ads are 6 and 1, and even ad 3 is higher than the highest RPI ad. Therefore, we’d want to take a look at those ads to see what in them is bringing in better qualified clicks.

We’d want to take a look at ad 5 as it has the highest average order value and see why. Does it have different cross sale or upsell items on the landing page or what about it is affecting average order value.

Ad 2 is a clear conversion rate loser. What about it is bringing in such terrible clicks for us? We’d want to make note of that ad and its idea as a warning in the future that the idea or promotion for that ad doesn’t work well.

Once we’ve examined the data, then we can pause all the losers and create a new ad to test against the winning ad.

The main time not to use RPI is when average order value isn’t a consideration. In those cases, you can rely on CPI as your main testing metric.

Revenue or profit per impression is one of the best ad testing metrics you can use since it is a simple number that lets you see which ad will lead to the absolute most revenue.

The largest downside of RPI testing is that it doesn’t look at account or ad level ROAS goals and if your revenue can vary widely across orders then it can get skewed by outliers. If you have hard ROAS targets, then you can use ROAS as a filter to remove ads that are below your targets and then pick your highest RPI ad as your winner; so many companies should use both ROAS and RPI testing metrics to choose their winners.

The other issue with RPI is that it relies on consistent data. If your orders are highly inconsistent or you have random outlier orders, then CPI may be a better testing metric for you.

There is not a ‘best’ testing metric for everyone.

There is a best testing metric based upon what you are trying to accomplish.

We’ve put together a quick reference chart to easily let you see what testing metric you should be using:

| What do you want to do? | The metric you should use |

| Increase conversions | Conversion per Impression (CPI) |

| Increase visitors | Click Through Rate (CTR) |

| Increase engaged visitors | Conversion per Impression (CPI) |

| Get the most revenue possible | Revenue per Impression (RPI) |

| Improve quality scores | Click Through Rate (CTR) |

There are two noticeable metrics missing from this list: ROAS and CPA.

Those two metrics should be filtering metrics and not winning metrics.

For instance, if you want the most conversions possible at a $35 target CPA; then you would use CPA as a filter and remove any ad that is above the $35 CPA target and then of the ads left, the highest CPI would be the winner.

These are the cases to use filtering metrics:

| What do you want to do? | Filtering metric | Winning metric |

| Highest revenue above a specific ROAS | ROAS | Revenue per Impression (RPI) |

| Most conversions under a target CPA | CPA | Conversion per Impression (CPI) |

In layman’s terms, statistical significance is the how likely a result is caused by something other than random chance. Essentially, this is how confident you are in the data that random chance didn’t cause winners and losers.

There is a relationship between Statistical Significance and minimum data (which we’ll cover later).

For instance, if you flip a coin 4 times, there is a 1/16 chance that heads will show up all 4 times. Yet on the 5th throw, there is still only a 50% chance that you’ll receive another heads. That’s because each time you flip a coin, there’s a 50/50 chance that you will see a heads or a tails. However, on consecutive throws, you need to take in the variables of the previous throws to determine the chance of seeing heads 5 times in a row (which is 1 in 32). This is why we need a certain amount of minimum data before we calculate confidence factors.

Eventually, the odds catch up and after 100 flips, you’ll probably have 47-53 heads assuming it’s a regular coin. If after 100 flips, you had seen heads 90 times, you are either on a very odd trend (and should go to Vegas) as that result is highly improbable or the stats say that your coin isn’t regulation and you are playing with a coin that is not properly weighted.

In fact, if you throw a coin 2,000,000,000,000,000,000,000,000,000 times or 2×1027 * – odds are that you will have 90 heads in a row at some point in time, which is purely due to chance. However, if you were to look at the entire sample set and not any one streak of numbers, you’ll see that heads and tails have each come up 50% of the time.

When you are picking your confidence factors for any one ad test result, you’re really saying, “how confident am I in these results that this result is meaningful and not due to chance?”

As your ads are the only part of your account that searchers see, when you pick winning and losing ads, you want to make sure that you are confident in the results and that you aren’t picking winners due to chance.

We’re often asked about confidence factors and how confident someone should be in their results before they take action; so we’ve made a handy reference chart based upon types of keywords:

| Term Type | Minimum Confidence |

| Long Tail Keywords | 90% |

| Mid data terms | 90% – 95% |

| 3rd Party Brands you Sell | 90% (small brands) to 95% (large brands) |

| Top Keywords (the ones you watch daily) | 95% – 99% |

| Your Brand Terms | 95% (unknown brand) – 99% (well-known brand) |

The overall rule is simple: The more important a word is to your account, the higher you want the confidence factors to be before you take action.

According to expert statisticians, you never want to be less than 90% confident in your results before taking action.

Odds are, you have segmented your account into various campaigns. Some campaigns are branded, others are long tail, and yet others are information terms, ‘hero terms’, competitors, and so forth. Therefore, its useful to just make a note of your minimum confidence level by campaign type.

Now the next time someone wants to discuss confidence factors, there’s just a few rules to keep in mind for the conversation:

The other data point that goes hand-in-hand with statistical significance and confidence factors is minimum data. This is the least amount of information that you want to use before determining if your results are significant or not.

Minimum data is the smallest data set you should use before calculating statistical significance.

If your ad tests don’t have enough data, then you shouldn’t pause ads or make adjustments based upon the data since there is a high likelihood any differences you see are due to chance and not actual patterns within the data.

For instance, this is a test result after 97 impressions:

|

Ad |

Impressions |

Clicks |

CTR |

Confidence |

|

Control |

40 |

1 |

2.5% |

|

|

Ad 2 |

33 |

5 |

15.15% |

97.03% |

|

Ad 3 |

24 |

0 |

0% |

15.57% |

In purely math terms, we do have a 97% confidence that ad 2 will be a winner. If this was a static data environment where the data that comes later is similar to the data that came before, we might take an action. However, search is a dynamic environment and it’s obvious that 97 impressions is not enough data (although, any online calculator will tell you it is).

Here’s the exact same test after 3163 impressions:

|

Ad |

Impressions |

Clicks |

CTR |

Confidence |

|

Control |

1023 |

23 |

2.25 |

|

|

Ad 2 |

993 |

29 |

2.92% |

82.9% |

|

Ad 3 |

1147 |

56 |

4.88% |

99.96% |

In this case, all of our ads have almost 1000 impressions, and we’re 99.96% confident in our winner (a different winner than at 97 impressions) and thus we can be confident that we can take actions on CTR based testing at this point in time.

At the low data levels, what you really want to avoid is having just one or two people significantly affect your data. For instance, if you have 100 impressions and 1 click, then you have a 1% CTR. If the next 2 people click your ad, your CTR goes from 1% to 2.91% CTR; which is a huge change and can completely affect which winning or losing ad you would have chosen.

When the data starts to grow, then you want to ensure that you have a sample size that is large enough so that a small percentage of searchers can’t significantly affect your data, which is why you want a larger and larger sample size the more impressions that an ad test generates within a given time frame.

Part of a minimum data consideration that does not exist within the realm of purely mathematical analysis is the variance of time.

For instance, imagine these three scenarios:

That’s just Monday, yet your Monday evening search probably happened on a mobile phone and your conversion is going to be sending yourself a work reminder to examine the result on Tuesday morning. Your Monday morning conversion was likely to be a whitepaper download or a phone call.

Now, that’s just Monday. If you were searching for vacation cruises, your Monday search was thinking about how much you want to escape the office and that same search on a Saturday afternoon might be planning with the spouse on a cruise vacation you plan to buy.

As timeframes change, so does search behavior – this is why we need to take into account not just the data, but the timeframe of the data. You should always use a minimum of a week of data. However, it is fine to use a month or even three months of data gathering before you take action.

When determining minimum data, there are two considerations:

We need to determine the testing metric before you know what data points to define.

As an example, if you are testing by CTR, your conversions don’t matter since CTR doesn’t use conversion data in its calculation.

Most metrics have both a required data point (as that’s the opportunity) and a secondary data point (action) used to calculate that metric.

For instance, click though rate is the ratio of impressions to clicks. You must have an impression to get a click. Thus impressions are mandatory but clicks are optional.

In some cases, you might not want to define the optional metric. For instance, let’s say we’re running two ad tests with this data set:

In this test, we’re confident that ad 1 is the better ad and has achieve over a 90% confidence interval. However, if we defined a minimum of 25 clicks, we’d still be waiting for results since ad 2 hasn’t hit that number yet. When you define the optional data points, you might wait longer to achieve results if one of your tests is significantly below average (in this case a 10% vs 1% CTR).

With minimum data, every ad in the test should hit the minimum data before you look at the information – not the test combined. As there are two ad rotation options, which we will cover later, it is common that not all ads within a test have the same opportunity, and thus each ad should meet the minimum requirements before you examine your confidence levels.

As timeframe is highly important to any test, all metrics should be using a timeframe minimum of at least a week; although, using monthly data works just as well.

Here’s the minimum data that you should define by testing metric:

| Metric |

Impressions |

Clicks |

Conversions |

Timeframe |

|

CTR |

Yes |

Optional |

Yes |

|

|

CPA |

Yes |

Yes |

||

|

Conversion rate |

Optional |

Yes |

Yes |

|

|

CPI |

Yes |

Optional |

Yes |

|

|

ROAS |

Yes |

Yes |

||

|

RPI |

Yes |

Yes |

We’re often asked to suggest minimum data amounts. There are times I’m hesitant to give out numbers because not everyone should be using the same numbers.

If you have a brand term that is searched 1 million times a week, you should be using at least a million impressions as your minimum. For many brands, they aren’t searched 1 million times in a year, and should be happy with 10,000 – 100,000 impressions before they examine their confidence levels.

These are MINIMUM DATA recommendations. It is OK to use higher numbers than these.

Minimum Data Recommendations for Most Companies:

|

Impressions |

Clicks |

Conversions |

|

|

Low Traffic |

350 |

300 |

7 |

|

Mid Traffic |

750 |

500 |

13 |

|

High Traffic |

1000 |

1000 |

20 |

|

Well-known brand terms |

100,000 |

10,000 |

100 – 1000 |

As your campaigns are often segmented by brand, product terms, long tail, etc – the ads within each campaign can generally use the same minimum data. You will often use different metrics, minimum data, and statistical significance factors for different parts of your account.

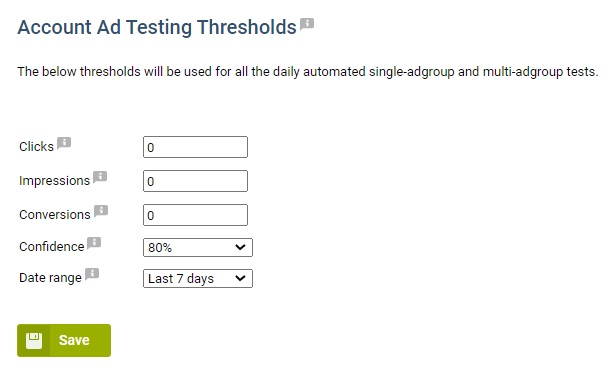

There are times when you will run an ad test; but the test is too similar or users don’t react much differently to your test variations and you will never achieve statistical significance.

If you only define minimum data and minimum confidence factors; these types of tests can run for years and you will miss an opportunity to further increase your conversions.

Therefore, you not only want to define minimum data, you also want to define maximum data.

If your ads hit your maximum data and have not achieved your minimum confidence levels, then you need to end the ad test and move on.

There are usually two ways to define maximum data:

Defining both minimum and maximum data for your ad tests ensure that you are striving to find actionable information even if that action is to just end a test as the results are not valid and start from a different hypothesis.

For Adalysis users, we automatically alert you to test results that are above minimum data thresholds and have been running for at least 3 months and have not achieved your minimum confidence levels. There’s no need to worry about defining this information. If you are testing within Excel or another system, ensure that you are defining maximum data so that you don’t have ad tests running that are not going to produce any results so that you’re always striving towards improving your performance.

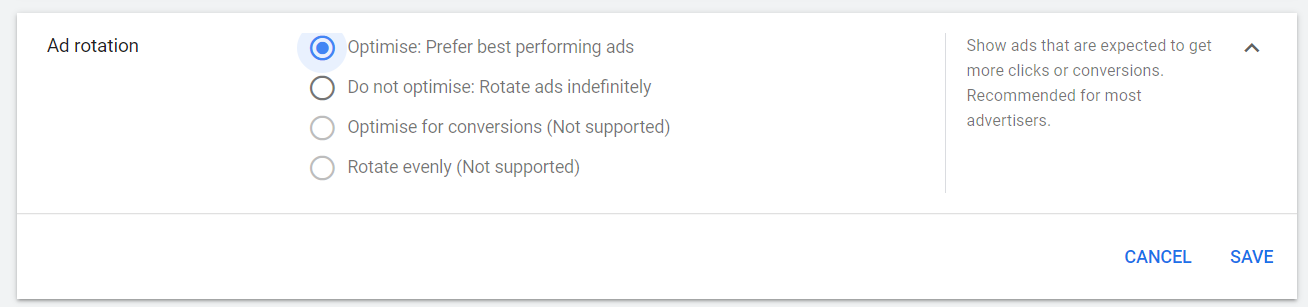

If you have multiple ads in an ad group, your ad rotation settings will determine how often each ad is displayed. Based on your testing and your favorite metrics, you should consider the rotation setting you are using and how that affects your ability to receive statistical significance data to make testing decisions.

After two of the four rotation options were retired in 2017, there are now only two ad rotation settings you can choose for your Google Ads campaigns:

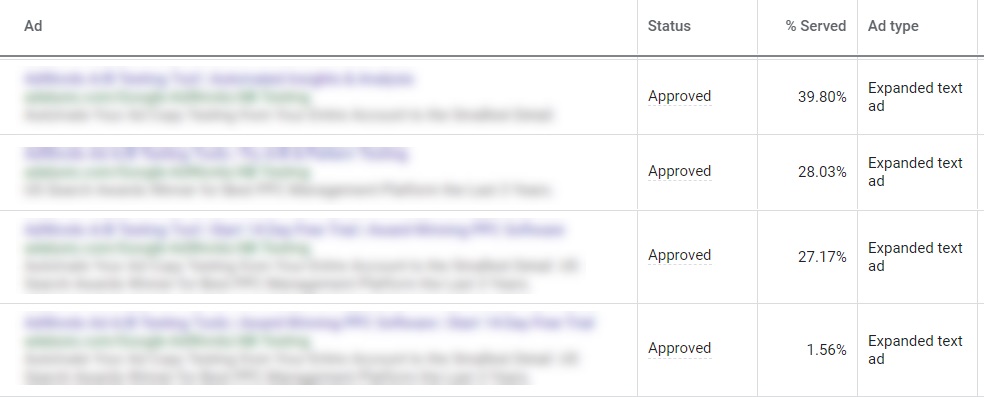

The ad served percentage shows you how often each ad was served across your account, campaign, or ad group.

When examining this data, it is crucial to keep in mind the time frame you are reviewing. If you have paused or deleted ads that were active during the timeframe you are examining, then your ad served percentages may not add up to 100% unless you show those ads.

In addition, it is useful only to examine the data when all the ads were running at the same time. If you created an ad one month ago; but you are looking at the last three months of data; of course, it will look like the newer ad doesn’t have the appropriate ad served percentage; and it can’t as it wasn’t active for two of the three months you are examining.

Any ad test should have a minimum amount of viable data, such as a minimum amount of time, clicks, impressions, and conversions. These may vary depending on the type of metrics you are using for ad testing and the type of keywords you are testing (such as brand vs. product).

When your ad served percentages are skewed towards a single ad, the other ads receive fewer impressions. Since they have fewer impressions, these other ads also receive fewer clicks and conversions. Since these ads are receiving less data, it takes longer for those ads to build up enough minimum viable data to make statistically significant decisions. You can collect the data faster with the right ad rotation setting.

If you use Google automated bidding, this is the only option you have. Even if your campaign doesn’t have this setting chosen explicitly in the settings, Google uses the optimize setting and chooses how to serve your ads.

Due to how ads are served unevenly, using this setting generally makes your ad tests take longer to reach statistical significance. This setting will sometimes display the incorrect ad the most, which can lower your clicks and conversions. Thus, you want to ensure you are testing ads, choosing winners, and pausing losers when using this setting as the worst-performing ad can end up with the most impressions.

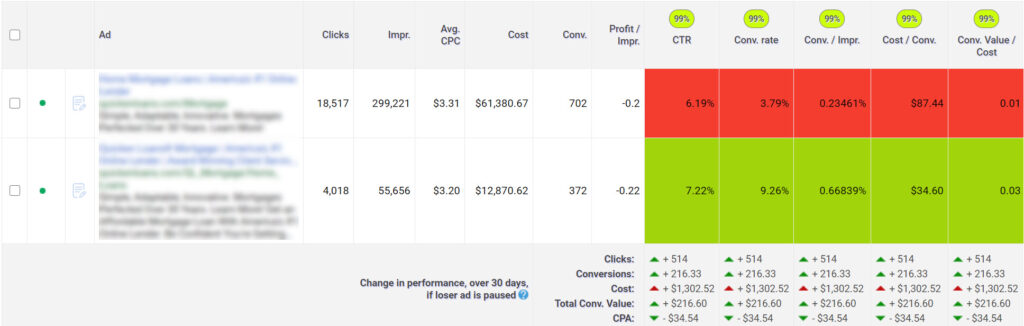

This example shows how the ad with the best data in every metric was served 55,656 times versus the ad that is a statistically significant loser in every metric being served almost 6 times as often at 299,221 impressions.

If the company just pauses the losing ad, they’d see their clicks and conversions immediately increase. This is why you need to watch your ad tests when using optimize as once Google’s machine learning decides which ad to show the most often if the data shows it was an incorrect decision, the machine rarely fixes the ad serving problem.

If you are bidding manually, meaning you are setting bids by hand, using a script to set your bids, or using a third party bid manager, then you should use ‘Do not optimize: Rotate ads indefinitely’.

This is the best ad rotation setting to use with your ad testing as all the ads have a higher chance of getting an equal share of the impressions.

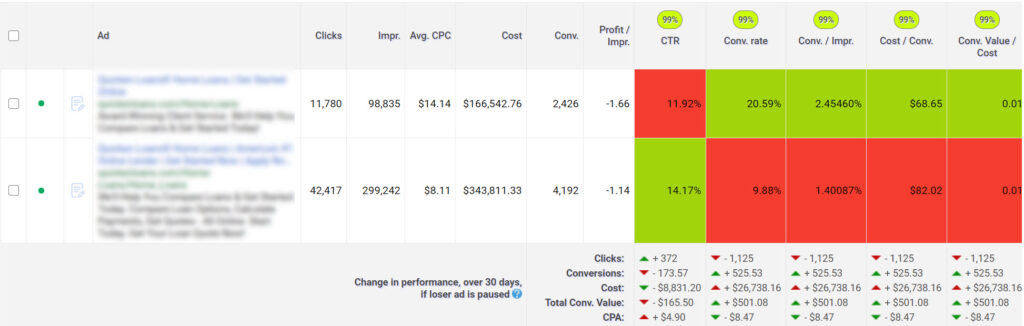

Let’s look at another example. In this ad test, there’s one ad that’s a winner by CTR and another ad that is a winner in every other metric. If you were truly being optimized, then the ad with the highest Conversion per Impression should be the ad shown the most often.

In this case, the ad with the highest CTR is being displayed 3 times as often as the ad with the highest conversion rate and conversion per impression.

When you have one ad with a higher CTR than another and yet another ad with a higher conversion rate or conversion per impression; Google often defaults to CTR over other metrics.

In this case, switching to ‘Do not optimize’ would ensure your ads get more or less similar exposure. This change would lead you to quickly finding out which ad will provide you with more conversions and which ad needs to be paused as it is much worse in most metrics.

In addition, if you introduce 5 or more ads in an ad group, Google’s ad serving can become very confused and ads seem to be served randomly as opposed to having identifying the best ad to serve and serving that ad the most often.

For example, in this ad test, the ads with the lowest impressions (the chart is sorted highest to lowest impressions) are the winners in CTR or the other metrics where we’re testing. Yet the ad with the overall worst data is being served more often, and the ads that aren’t the best in any metrics have significantly more impressions (107,335) than the ad that will give us the most conversions (15,107 impressions). When you have too many ads in an ad group, Google gets confused and doesn’t even fall back on CTR or conversion per impression when using optimized ad serving.

This is also a common issue when new ads are introduced. With optimize ad serving, sometimes the new ads rarely get impressions and a chance to show what they can achieve.

In all of these cases, if you are serious about ad testing, you should be using ‘Do not optimize: Rotate ads indefinitely’ in campaigns with manual bidding (i.e., not using Google automated bidding strategies). With this ad rotation option, you get faster ad testing results, and across ad groups your ads are served more evenly making multi-ad group testing very accurate for getting insights into large sets of ads.

However, if you are ignoring your ad tests and not adding many new ads, then using the ‘Optimize: Prefer best performing ads’ can be OK to use as Google making some good and bad choices is better than doing nothing.

If you are using Google’s automated bidding, then you don’t have a choice over which ad serving option to use. Therefore, you want to watch your ad tests closely to ensure that your favorite ads are being served the most often.

Taking action is fairly simple. Once you have defined:

Then you can follow a simple flowchart to see if your action is to wait or take action:

Further insights is a vague notion; however, there is much to be gained by ad testing.

Here are some examples:

Ad tests give you an amazing amount of insight about how users interact with your ads. These insights can be used for other parts of your marketing. It is more common to leverage insights from multi-ad group tests than single ad group tests in these ways since multi-ad group tests include a lot more keywords and ad group than single ad group tests do.

The actions themselves are not very difficult. The trick is to first determine your criteria for winning and losing ads so that you know when to take an action.

The overall steps to ad testing are:

Once you start testing your ads, you can learn amazing things about how your visitors interact with you creatives and constantly improve your overall PPC performance.

If you want to automate many of these tasks and make ad testing incredibly simple, try Adalysis for free.

Share Around the Web